"Adventure on the Colorado, by Al Morton, comprises 1,600 feet of film and (at twenty four frames a second) forty eight minutes of screen time. In it, six men in two boats travel down the Colorado River from Moab, in southeastern Utah, to Lee's Ferry, in northern Arizona. Taking fifteen days, the trip covered some 300 miles, forty of which were through cataracts already claiming twenty nine lives. These are the bare and simple facts of the case. But these facts cannot begin to tell the story of Mr. Mortons epic adventure. And mind you, we are not concerned here with the breath taking dangers of the trip itself — although these alone were awesome and challenging. We are concerned only with Mr. Morton's filming adventures and the bright, indomitable story of them as recorded so stirringly in his film. That story is one of inflexible resolve against all compromise, even in the face of well nigh impossible circumstance. At one point in the picture, Mr. Morton shows us a rugged and precipitous approach to the river known as "Hole in the Rock." It was through this narrow passage that, years ago, a little band of Mormons, sent to colonize the San Juan country, brought their wagons and their belongings. In laces where the chasm had narrowed so sharply as to block the cavalcade, they dismantled the wagons and packed them through on their backs. For they had set out to cross the river — and cross it they did. Mr. Morton's filming resolve must have been of that same high order — almost religious in its intensity. As the down-river journey grew ever more arduous, you waited with sympathetic understanding for those not quite perfect scenes which the incredible conditions must surely dictate. You were ready to make allowances, to accept the imperfect as relative perfection --under the circumstances. Not so with Mr. Morion. There was no compromise with quality in the Morton picture plan. He set out to film the river, and film it he did. Adventure on, the Colorado is a moving and splendid epic, recording both a gallant adventure and a glowing achievement." Movie Makers, Dec. 1947, 513.

"In Caineville, Glen H. Turner has now turned his camera on a Western ghost town, and with moments of sheer movie magic, he has brought it to life again. The slow turning by the wind of the leaves of an abandoned school book, and the slow pan to initials carved on a schoolhouse desk, evoke as if he were alive the youngster who carved them. In another scene, done with consummate smoothness, Mr. Turner shows an abandoned street on which a schoolboy, with books over his shoulder, slowly materializes into solid form — and then dissolves again into thin air. Surrounding Caineville always are the brooding mountains and the ever-encroaching river which implacably seeks to destroy the last vestiges of the crumbling village. Caineville is a triumph of imaginative creation over static material." Movie Makers, Dec. 1953, 320.

"Once again Harry W. Atwood has used the desert locales of the Southwest and his mastery of outdoor color filming to mount a dramatic and exciting action picture. Although The Carabi Incident is truly an incident rather than a full-fledged photoplay, it does manage to include an abandoned mine, a lost prospector, a worried young girl and her companion — and both a happy and a tragic ending! The production is enriched with Mr. Atwood's usually fine selection of camera angles and suspenseful editing. For these reviewers, however, an excess of dialog subtitles was a drag on the film's development." Movie Makers, Dec. 1952, 341.

"Whatever that intangible thing called atmosphere may be, Harold E. Remier has created it — out of airy nothings, to judge by what he says — in his astounding photoplay, Diary. Here, in all its hues, in all its beauty, in all its tradition of courtesy and profound courage is the America of the late Nineteenth Century, told through the medium of a woman's devotion. A Southern mansion is the first setting, then the frontier. Fortunes rise and fall as the war flames. Costumes and settings of the 1890's are recreated with fidelity. Wagons collapse in the wilderness; stone houses are built; a silver mine is uncovered. And the cost, for this epic achievement, exclusive of the 8mm. film, was the staggering sum of ten dollars! Diary is particularly noteworthy for naturalness of its lighting. However he managed it, Mr. Remier. with two large flood bulbs, somehow succeeded in making each scene appear to be illuminated by the hand lamps and chandeliers visible within it. The moonlight elopement is glamorously effective; and even candlelight is simulated with success. So, in all, the picture is a distinguished achievement — a portrayal, not only of a past century, but of a part of our American heritage." Movie Makers, Dec. 1940, 577.

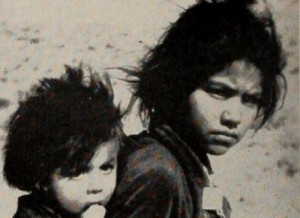

"In Dineh, Henry E. Hird. whose broad sympathies have brought his talents to bear upon so many unselfish projects, has taken up an effective cudgel in behalf of the Navajo Indians in the United States. Dineh, "The People," is the Navajo word for their tribe. Mr. Hird went to the Navajo country with the simple purpose of making a record film of that proud and self reliant Indian people. From what he saw there and from his conversations with many Indian citizens, he became convinced that now, if ever, the Navajos need understanding and practical aid. His film, therefore, not only accomplishes his primary aim — of recording an interesting racial group — but, in scenes and particularly in narrative, it pleads the economic and social case of the Navajos. Mr. Hird's cinematography is of very high order, as is usual in his films. His continuity is intelligent and interesting, and his narrative is a fine plea for a worthy segment of the citizenship of the United States." Movie Makers, Dec. 1947, 514.

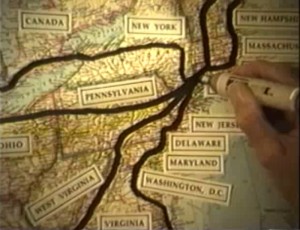

"During five summers from 1957 to 1961, the five-member Barstow family of Wethersfield, Connecticut, set out to visit all 48 of the then United States of America on a series of month-long camping trips. Part II showcases "America's Wonderlands" with 18 National Parks and other exciting attractions in the great Northwest and Southwest." Archive.org

"In Grand Adventure Louise Fetzner presents a lively record of a daring run through the wild rapids of the Colorado River, as it courses the Grand Canyon from Lee's Ferry to Lake Mead. While thrilling scenes of the intrepid boats and boatmen provide the film's drama, Mrs. Fetzner has not overlooked human interest sequences on the small daily activities of these hardy adventurers. Generally good in photography and editing, the film falls off in pace somewhat in its latter portions. And perhaps the frequent inserts of a title-map of the Colorado are more hindrance than help in what is essentially an action picture." Movie Makers, Dec. 1952, 340.

"Grand Canyon Voyage is the record of how seven daring people in three tiny boats ran the Colorado River from Lee's Ferry in Arizona, through the awesome gorge of the Grand Canyon, to Lake Mead in Nevada. The trip itself was the exciting and gallant climax to four years of dedicated effort by Al Morton. Ideally, this film record of the trip should be infused with this same excitement, this same sense of gallant adventure. That it is not consistently so inspirited will be a source of sincere regret to all who know Mr. Morton. But perhaps no motion picture of this dangerous, demanding river run could recreate this spiritual overtone. The physical odds against filming were too great, too overwhelming, for controlled camera work and integrated continuity. Survival itself became more important than an image of it. Al Morton, we believe, has done a supremely difficult job far better than would the most of us. He has done it as well, surely, as any cameraman living." Movie Makers, Dec. 1951, 411.

"Al Morton has conquered another river. This time it is the unruly turbulence of the Green River in Utah. Not content to be simply a passenger, Mr. Morton built his own boat (and named it Movie Maker!) for shooting the rapids, one of three craft making up the river party. Green River Expedition is a record of lazy, sunny days on quiet stretches, of motor trouble and of scenery along the banks, of back breaking portages where the rapids are too dangerous to maneuver, and finally of the breath taking excitement of riding the tumultuous waters. To partake of this dangerous sport would seem accomplishment enough, but Mr. Morton puts it all on film as well, in about as sparkling, steady photography as one will ever see. The narrative accompaniment, while informative concerning the technique of river boating and the historical background of the surrounding country, seemed overfull. It is enough, in parts, to devote one's whole attention to the thrilling action on the screen." Movie Makers, Dec. 1950, 464.

"A delightful film of the home is A Greene Christmas, produced by Mildred Greene. Here is a record of a domestic Christmas that may well serve as an exemplar to other movie makers who are tempted to wander far afield. No startling new stunts in technique or effects of continuity are displayed, yet the film is so homelike, pleasant and sincere that it commands recognition as an achievement. Naturally, however, all departments which contribute to the completion of the film are more than adequately handled. The interior lighting, which resulted in perfectly exposed color shots in the familiar home settings, is noteworthy. Special recognition should be accorded the successful, well exposed shots of the subjects out of doors at night in one sequence. All the actors, members of her immediate family and friends, including the producer, were naturally and pleasantly shown, but the palm for outstanding characterization must go to Miss Greene's mother, who played the part of herself in a most delightful and unaffected way. The preparation of the color titles for this film deserves special mention because of their perfect exposure, fine backgrounds and outstanding arrangement of metal script letters. (Miss Greene tells about making A Greene Christmas in Stretching Christmas, in this number of Movie Makers.)" Movie Makers, Dec. 1939, 609.

Total Pages: 2