"Stephen F. Voorhees's 400 ft. travel film of Italian architectural scenes deserves placement in this list because it combines three factors but rarely brought together in pictures of this type. First, the photography is extraordinarily good, not only with reference to the routine requirements of exposure and focus but because it is artistic throughout and the composition never descends to the casual or the "snap shot" level. Second, Mr. Voorhees's film has a natural and easy continuity, jogging amiably through Venice and its environs, much as a traveler might do himself, pausing for a bit of incidental human interest and catching a scene that the filmer felt was unusual but presenting it without any preliminary flourishes, as one friend who might have said to another in the course of a stroll, "Don't miss that, by the way," pointing to something seen on the way. Last of the three things, so unusual to find combined, is a professional study, made by the filmer, himself a great architect, preserving those details which he wished to bring from northern Italy for later possible use. The great Colleoni statue is studied from many angles. Details of tiles and other wall ornamentations are offered and buildings are presented from one viewpoint after another. Yet all of this is done unpedantically and the nonprofessional audience is not aware that this subtle architectural record is more than a delightful travel film." Movie Makers, Dec. 1931, 658.

"The film begins at a women's hairdressers. The manager asks one of the hairdressers to dinner that evening but she refuses as she has a customer, Mrs Blowers, who requires longer visits. At this the manager appoints Jane, a fellow hairdresser to take the appointment. Jane looks at the portrait of her fiance. We follow as the portrait dissolves into the real man. He works with cars and is informed that he has lost his job. Back at the hairdressers and Mrs Blowers arrives for her appointment. What starts as 'just a trim' becomes a longer matter. The clock shows 7.15 PM, closing time at the hairdressers. Jane loses her temper with her customer and insults her. The woman responds, stating that she will be making a complaint. On her way out Jane is informed that her customer was a stakeholder in the business. Jane meets with her boyfriend and they agree to share their bad news at a café. Later Jane discusses her situation with her friend but still despairs at her predicament. We see her writing a letter to her fiance, returning his ring and ending their engagement. She posts the letter. The next day at work Jane is informed of her week's notice. She begins cutting a young girl's hair. Outside one of the employees has alerted all about a fire. Jane notices smoke at her door. She covers the child and carries her out of the building but collapses from the smoke. The next sequence shows her in hospital. She is visited by her boyfriend and we see that she is wearing her engagement ring. At home recovering, she is visited by Mrs Blowers. This is where the film ends abruptly" (MACE Online Archive).

"'Japan and Its People,' Dr. Roy Gerstenkorn's educational class winner, was a pictured visit to the homes and temples of Japan. Ignoring the cities in his search for the story of the Japan that is not known to the average visitor the doctor penetrated the towns and smaller communities. His picture was awarded a high rating on its photography as well as on his treatment of the subject. After the showing of this picture before the Los Angeles Motion Picture Forum last summer the local school authorities requested and received permission from the doctor to make a duplicate of it for school purposes." American Cinematographer, Jan. 1938, 27-28.

"In L'Ile d'Orléans, Radford and Judith Crawley cross a bridge and come back. But they cross a bridge with a difference, because what they see and what they make us see on the other side of that bridge is the inner essence of a withdrawn people, who proudly conserve the memory of things past in the realities of things here. The Maxim Award winner opens a door into a region of Eastern Canada — the Island of Orleans — where old French and old Canadian folkways are lived placidly and with dignity. Actually, the camera crosses a very modern bridge at the film's beginning and returns over it at its end. But, once in L'Ile d'Orléans, in the hands of the two Crawleys, this Twentieth Century box of wheels and gears spins a tale of yesterday, even if it pictures just what its lens sees today. The landscape and the old houses, some of them there for more than two hundred years, set the decor, after which we come to the dwellers in this separate Arcady. They do, with a delightful unconsciousness of being observed, the things that make up their daily lives, and, when invited to take notice of the visitors, they do this with a fine courtesy that is the very refinement of hospitality. Mr. and Mrs. Crawley devote a liberal part of their footage to a careful study of home cheese making, in which camera positions and a large number of close shots turn what might have been a dull and factual record into something of cinematographic distinction. The highlight of the Crawleys' film is a leisurely and sympathetic watching of what is the highlight of life in l'Ile d'Orléans — the country Sunday. We see different churches, all of a general type, but each with its essential neighborhood individuality. Finally, one of these is singled out for an extensive camera visit. Bells ring and the country priest is shown with his gravity and solemn courtesy. The countryside comes to life with its church bound inhabitants who wind over the simple roads slowly yet purposefully and with the assurance of those who know that the land is theirs as it was their fathers'. With such pictures of everyday life, scored with appropriate music for double turntable showing, Mr. and Mrs. Crawley have etched an epoch, in a record which can stand on its own feet with good genre description in any art form. With not a single concession to sentimentality — as should be the case in honest work — but with a sure feeling for that which reaches out for the finer emotions, they have shown us what they found across the bridge. Here is personal filming at its best." Movie Makers, Dec. 1939, 608-609.

"Within the brief confines of Lady on June Street, Leo Caloia presents a satisfying example of the personality film worked out in story form. Faced with the common problem of family filming, he has resolved the riddle with imagination, humor and marked cinematic ability. The "lady" in question is pictured as a lazy, luxury loving wife, spiritually eager to be the best of helpmates, but physically enslaved to satins and sweetmeats. Dozing, as she regards with languorous ambition an advertisement for homemade shortcake, she dreams vividly of a sweet but unaccustomed success with pot and pan. Crash! In her dream, the lady slips, and her magnificent shortcake slithers across the kitchen linoleum. Bump! In reality, she has rolled sleepily from her couch, to awake with a thud on the living room floor. The film fades swiftly as she hurries the tops off canned beans and sauerkraut." Movie Makers, Dec. 1939, 632.

"Children and pets are generally lovable and always interesting; but filming them is not a simple task, as many amateurs have found out. Raymond J. Berger, in Lassie Stays Home, accomplishes it with a sure touch and an ease that will be the envy of his fellow filmers. The excellently planned story tells of a lost child who is found by Lassie, the loyal canine family member, after the baby's somewhat older sister hunts her frantically. No adult appears in any of the footage; and remarkably enough, one does not sense the directing mother, just out of camera range. The whole movie goes forward as if the children and Lassie were entirely alone, with the camera miles away. Here is 8mm at its best and here is a film that every amateur would be proud to have made." Movie Makers, Dec. 1945, 494.

"Among the ten best, The Last Entry, running seven reels 16mm., is one of the most ambitious amateur photoplays ever undertaken and completed. The plot, requiring many elaborate interior sets, is based on a mystery story that opens with a house party. While a room is darkened for the projection of amateur films, one of the guests is murdered and all present may be suspected equally. The detective handling the case uncovers the fact that the murdered man, an author, has lived on blackmail effected by threats of exposure through publication, which throws suspicion on several of the guests of the house party who were discovered to be his victims. However, in the end, the murder is solved by screening the same pictures that were on the projector when it was committed. Although this plot offered great difficulties in the direction of large group scenes, the creation of the necessary lighting effects and the interpretation of the actors' roles, it is beautifully and suavely handled. In the film are several lighting treatments that may be listed as among the most effective ever achieved by amateurs. One chase sequence staged through long corridors, a large, dimly lighted attic and on the roof of the mansion at night in the rain, can be likened only to the effects secured in the best professional mystery photoplays. James F. Bell, jr., ACL, was director with Charles H. Bell, ACL, and Benjamin Bull, jr., ACL, cameramen and Lyman Howe, ACL, in charge of lighting." Movie Makers, Dec. 1932, 537-538.

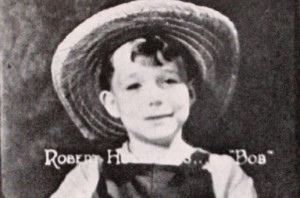

"'Life,' by H. B. Hutchings, given the highest recognition for Home Movies, is the sort of picture that the 16mm camera was made for. It is a day in his son's life and contains many effects which were undoubtedly secured with one of the more modern cameras." American Cinematographer, Dec. 1933, 321, 342.

"On an actual Protestant missionary who brought Christianity, education, and medical aid to an illiterate, pagan tribe in the Belgian Congo." National Archives.

"This year, Ten Best welcomes a baby picture to its select circle. Out of the large number of personal and family films submitted to the League, Linda represents the ultimate in child movies. Here, in less than ten minutes of running time, unfold some of the high lights of the first few weeks of a baby's life. Following a carefully planned scenario, Richard Fuller shows himself well acquainted with motion picture technique. Lovely settings are accentuated by superb lighting. Pastel pinks and blues, colors intimately connected with the nursery, predominate. Fine cutting, well chosen camera viewpoints, effective use of dolly shots and double exposures all attest to a sound knowledge of cinematic expression. Above all, there is a feeling of quality and good taste. At the advent of a tiny stork, ingeniously controlled by wires, Mr. Fuller begins pacing the floor and lighting one cigarette after the other. Then, the routine of Linda's early days is set forth in charming fashion." Movie Makers, Dec. 1941, 564.

Total Pages: 29