"No matter how one feels about the outside cover of a magazine, George E. Valentine's The Inside Story of the Outside Cover will be a surprise. If you think that the production of four color engraving plates is a simple matter, you will do some quick revising of your thinking. If you have a certain admiration for the technical skill that goes into such work, that admiration is likely to be heightened by Mr. Valentine's step by step story of the creation of a four color magazine cover. Aside from the story it tells, Mr. Valentine's film is a real technical achievement because of the working conditions under which most of the shots were of necessity filmed. His peak sequence — a proof-press run analyzed in slow motion — was achieved by mounting the camera directly on the moving press. When you can do that, you're good." Movie Makers, Dec. 1947, 539.

"Stephen F. Voorhees's 400 ft. travel film of Italian architectural scenes deserves placement in this list because it combines three factors but rarely brought together in pictures of this type. First, the photography is extraordinarily good, not only with reference to the routine requirements of exposure and focus but because it is artistic throughout and the composition never descends to the casual or the "snap shot" level. Second, Mr. Voorhees's film has a natural and easy continuity, jogging amiably through Venice and its environs, much as a traveler might do himself, pausing for a bit of incidental human interest and catching a scene that the filmer felt was unusual but presenting it without any preliminary flourishes, as one friend who might have said to another in the course of a stroll, "Don't miss that, by the way," pointing to something seen on the way. Last of the three things, so unusual to find combined, is a professional study, made by the filmer, himself a great architect, preserving those details which he wished to bring from northern Italy for later possible use. The great Colleoni statue is studied from many angles. Details of tiles and other wall ornamentations are offered and buildings are presented from one viewpoint after another. Yet all of this is done unpedantically and the nonprofessional audience is not aware that this subtle architectural record is more than a delightful travel film." Movie Makers, Dec. 1931, 658.

"Jello Again is an entertaining film, produced entirely by animation, that stands by itself even when the special work necessary to produce it is discounted. This Kodachrome subject, filmed by Carl Anderson, is made entirely in stop motion with puppet actors, an exceedingly difficult job. The excellence of the handling of the puppets and accessory properties, together with the imaginative quality of the settings, makes the subject an outstanding one. Here and there throughout the film, there are certain indications of unevenness in exposure on the "over" side, but, because of the real achievement embodied in the film as a whole, this very slight flaw may well be overlooked. The models used in the action were most cleverly constructed and colored, and the variety of camera angles employed was especially appropriate to the subject from the point of view of presenting the material advantageously." Movie Makers, Dec. 1939, 634.

"Renowned Hungarian violinist Jelly D'Aranyi steals the scene, and brings a swirl of glamour to a cold Manchester day, as she entertains young Ruth Behrens in the family's garden. Jelly always stayed at Holly Royde, the Behrens' family home, when she performed with the Halle Orchestra. Look out for Ruth's sister Mary, confined to the house with a cold, and watching the fun through opera glasses." (BFI Player)

"This film is dedicated to all lousy golfers who give up the game daily..." Fully narrated film of a round of golf at the [Cape Neddick?] Country Club in Ogunquit, Maine. Foldfilm.org

"Kaleidoscopio, by Dr. Roberto Machado, is a brilliant and provocative study in abstractions, filmed in its entirety through a kaleidoscope. Dr. Machado's cinematic extension tube, however, is quite obviously not the familiar small toy of one's childhood: in one sequence, delicate human fingers are deployed before the device, while in another a set of colored, kitchen measuring spoons do a gay dance in multiple. The lighting — which traditionally was transmitted only through the base — ranges from that type (through gleaming balls of crushed cellophane) to reflected illumination on an assortment of children's marbles. Billed by its producer as a "film musical," Kaleidoscopio is indeed instinct with strong rhythmic patterns and pulsations. The picture is an exciting and imaginative advance along the ever widening frontiers of personal motion pictures." Movie Makers, Dec. 1946, 471.

C’est à l’automne 1937, au retour de l’exposition universelle de Paris, qu’Omer Parent entreprend la réalisation de l’œuvre expérimentale La vie d’Émile Lazo. En réaction directe à la « loi du cadenas » émise par le gouvernement Duplessis, le titre de ce court-métrage réfère au tout premier film visé par cette nouvelle motion censurogène, imposée aux médias : The life of Emile Zola de William Dieterle (1937).

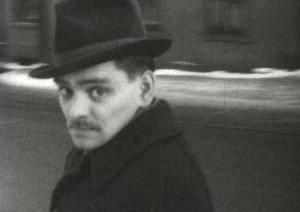

S’il s’agit là du premier film expérimental achevé par Parent, l’œuvre est également issue d’une collaboration amicale au sein de professeurs de l’École des beaux-arts de Québec qui se prêtent au jeu de l’acteur : la sculptrice Sylvia d’Aoust (1902-2004), la dessinatrice Arline Généreux (1897-1987), la graveuse Simone Hudon (1905-1984), le couple Madeleine Des Rosiers (1904-1994) et son mari Jean Paul Lemieux (1904-1990), tous les deux peintres. À cette petite bande — qui fréquente l’éphémère atelier du « Nordet » où le tournage a lieu —, s’ajoute Robert Lapalme (1908-1997), caricaturiste et illustrateur de talent au style immédiatement reconnaissable, seule figure à ne pas occuper alors un poste de professeur. Sorte d’électron libre, Lapalme, en plus de rédiger le scénario du film en écho à sa propre existence, y incarne le rôle d’Émile Lazo. Terminé au printemps 1938, ce film « amateur » porte sur la condition de l’artiste « moderne » vis-à-vis de l’académisme dont il cherche à se libérer.

Peu après sa création, La vie d’Émile Lazo a été projetée à quelques reprises lors de présentations publiques et particulières dont une visait, en 1941, à célébrer l’installation d’Alfred Pellan — meilleur ami de Parent — dans son nouvel atelier. Depuis cette époque, ce film, dont il n’existe que deux copies sur pellicule, est demeuré pour ainsi dire inédit, connu seulement par quelques amateurs et spécialistes. Zoom-out est fier de présenter cette satire, rare et burlesque.

In the autumn of 1937, upon his return from the Paris Universal Exhibition, Omer Parent undertakes the creation of the experimental work "The Life of Emile Lazo". In direct reaction to the "Padlock Law" issued by the Duplessis government, the title of this short movie refers to the very first film targeted by this new censorship motion imposed on the media: William Dieterle's "The Life of Emile Zola" (1937). Completed in the spring of 1938, this "amateur" movie deals with the condition of the "modern" artist in relation to academicism from which he seeks to free himself.

While this is Parent's first experimental work, it is also the result of a friendly collaboration among professors at the École des beaux-arts de Québec who lend themselves to the role of actors: sculptor Sylvia d'Aoust (1902-2004), draughtswoman Arline Généreux (1897-1987), engraver Simone Hudon (1905-1984), the couple Madeleine Des Rosiers (1904-1994) and her husband Jean Paul Lemieux (1904-1990), both painters. A little appart in this small group of artists and professors — who frequents the ephemeral "Nordet" studio where filming takes place— Robert Lapalme (1908-1997), a talented caricaturist and illustrator with a immediately recognizable style, is added. Lapalme, in addition to writing the film's screenplay in echo with his own existence, also plays the role of Émile Lazo.

Shortly after its creation, "The Life of Émile Lazo" was screened a few times during public and private presentations, one of which aimed, in 1941, to celebrate the installation of Alfred Pellan—Parent's best friend—in his new studio. Since then, this rare and burlesque satire, of which only two copies on film exist, has remained virtually unpublished, known only to a few enthusiasts and specialists until fall of 2022 where it was realeased online.

"In Lake Superior Landscape, the artist, Dewey Albinson, demonstrates his technique of landscape painting from the bare canvas stage to the climactic moment when the glowingly finished product is first exhibited. Shot by Elmer Albinson, the film is marked by vivid closeups and many changing angles, which help immeasurably to achieve a comprehensive sense of growth as the painting progresses. Producer Albinson understands the relationship that exists between the object, the artist and the painting; he has used his camera with accuracy and sensitivity to pass this understanding on to those who see his film." Movie Makers, Dec. 1947, 538.

‘Record of the building of a house. On screen title states "A specification for building a modern house in Dorset". The films proceeds through the following processes - Site inspection by architect and surveyor, clearing the site, laying trenches and adding concrete, bricklaying, placement of joists and lintels, installing outside staircase, building flat asphalted roof, foreman keeping an eye on works, adding steel balustrades, architect regularly inspecting, installing interior partition walls, installing internal staircase, electrically polishing downstairs wooden floors, painting, viewing the finished house’ (EAFA Database).

Total Pages: 14