A series of seven short documentaries about traditional handcrafted objects that are disappearing from modern society; an exploration through moving images of the altarpiece in the Assumption of Our Lady of Lekeitio Basilica; a pacifist fiction film where a child experiences the horror of war. These are just three examples of the hundreds of amateur films produced in the Basque Country since the late 1950s that the Basque Amateur Cinema project is recovering from oblivion.

For the past five months a team of students [Nerea Ganzarain Fuente, Andrés Fernández, Alfredo Ruiz, Irma Baldwin Mateo, Unai Ruiz, Arnau Padilla and Milica Jovcic] from the Elias Querejeta Zine Eskola (EQZE) in San Sebastian, Spain, have been working with researchers Clara Sánchez-Dehesa, Enrique Fibla Gutiérrez, and the Amateur Movie Database team in a project aimed at creating the first detailed map of amateur filmmaking in the Basque Country.

Since the history of amateur cinema in the Basque Country has not been written, we were faced with the perennial dilemma of organizing a research project from scratch: where to start from? We didn’t want to focus on a specific city or film club, since this would limit the scope of the comprehensive map we are trying to create. So, after some initial research into the extremely sparse literature on nonprofessional film culture in the Basque Country (Echevarrieta 1984; Zunzunegui 1985; Letamendi and Seguin 1997; Lauzirika and Rodríguez 2017), the local magazine Oarsao (Rentería) and other print sources, together with Sánchez-Dehesa’s knowledge of the amateur film circuit in the Álava region, we created a basic timeline of the development of amateur cinema with names of clubs, filmmakers and festivals.

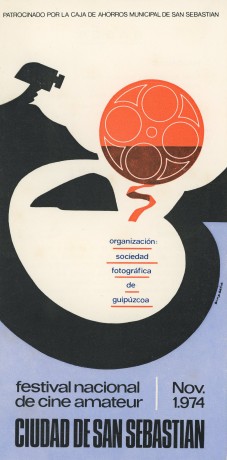

The length of this first list was already quite surprising, and it pointed to an extremely important history, spanning from the 1920s to the 1980s, that had been overlooked by Basque film scholars. We then divided the research team into three groups. Each of them focused on a film club from one of the three provinces that form the Basque Autonomous Community; Guipuzkoa (Cine club Renteria), Álava (Sección de Cine del Consejo de Cultura) and Vizcaya (Lekeitio Zine Bilera). We started following leads, making phone calls, visiting local archives, interviewing filmmakers, and collecting films, leaflets, and news clippings that had been stored in basements and attics for decades.

The results have exceeded by far the initial expectations of the project. In only a few months of research, we have counted at least 27 film clubs, 28 festivals, 108 filmmakers, and hundreds of film titles that we are trying to trace back to their physical copies. These numbers will only grow as the research process continues. Unfortunately, most of the films are yet to be located since the vast majority of amateur filmmakers kept them in their homes; some even forgot about them or threw them away when moving.

Tracking films down is a slow and arduous process, but the publication in the local newspaper El Diario Vasco of an article about the project has already proven very productive. Several former filmmakers and film club organizers have approached the EQZE and expressed their interest in bringing films and other materials that will eventually be deposited in the Basque Film Archive (Filmoteca Vasca), where others had already brought their films in the past.

This is a very important step in the preservation of Basque amateur cinema, since filming with Super 8mm meant having only one copy of each film due to the great expense and loss in quality that making duplicates implied at the time. This makes the amateur archive a particularly fragile heritage, since unless the authors preserved the original copies and stored them correctly, or transferred them to VHS or digital formats, they are lost forever (and the climate conditions in the Basque Country, with very high humidity values don’t help). One of the aims of the project is precisely to raise public awareness of the importance of recovering, preserving, and making accessible to the public the amateur archive.

As George Toles mentions in his evocative call for a history of film based on fragments, “The stubbornly alive particles and remnants of a forgotten movie have elective affinities with the larger, always unfolding utopian narrative of cinema at large” (Toles 2010, 161). In the absence of a professional film industry in the Basque Country that reflected the region’s cultural, linguistic, and social idiosyncrasy, amateur cinema became one of the most important vehicles of expression for local artists, enthusiasts, and future professional film directors.

This was especially the case in the last years of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship (1939-1975), during which peripheral nationalities and non-Castilian cultural and national identities were fiercely repressed and could only find refuge in grassroots or clandestine initiatives such as amateur film clubs, civic associations, or private homes. With the approval of the 1978 democratic constitution a process of gradual political devolution started, during which Basque culture, language, and institutions were recovered and reclaimed, leading to today’s Basque Autonomous Community (which has full control over culture and education).

Already in the 1960s, and fueled by the popularization of Super 8mm cameras due to their reduced cost and ease of use, amateur filmmakers gathered in film clubs, organized film festivals, and participated in national and international circuits of film circulation and exchange. These type of vernacular spaces were not as easily controlled by the police and censorship officials as the professional circuit, allowing for an unusual level of freedom of expression that was certainly not absolute (amateur film festival entries still had to pass censorship and could not overtly make reference to political issues) but that served an important purpose as a space of discussion and encounter for anyone that directly or indirectly opposed the dictatorship by thinking, and creating, freely.

In (substandard) cinema, everything was possible, and the bleak reality of political and cultural repression could be evaded, criticized, or simply forgotten for a few hours by making films. Miguel Ángel Quintana, who specialized in nature documentaries and animation films, recalled in an interview with the research team how he became fascinated by film when his parents bought him a rudimentary toy camera (most likely a Cine-Nic, which used 9.5mm stock). He recorded some images and then projected them over and over again below the staircase of his house, completely fascinated with the possibility of capturing and reproducing a reality of his own, and not from the state-controlled media or commercial films.

Likewise, María Jesús “Tatus” Fombellida explained to us how the usually closed-minded craftsmen that she recorded in her documentary series Gure Herria [Our Country] opened up to being filmed only after she projected the films she had shot of them in their own homes in remote areas of the Basque country. Before the creation of the Basque regional television ETB in 1982 (which was one of the most important milestones in the process of political devolution), these type of experiences through amateur and grassroot media were the only way to develop a vernacular visual culture.

In the following months we will analyze the information gathered, expand the research process to other clubs and filmmakers, write more articles on specific topics, and digitalize as many films as possible. Beyond the rescuing of the films themselves, a more important conclusion has emerged out of the first phase of the research project; amateur cinema was the most important locus of film culture in the Basque Country from the 1950s to the 1980s. But it hasn’t found a significant place in a film historiography that disregards noncommercial film culture as a mere hobby, instead of understanding it as a key player in the emergence of film culture in contexts without film industries but with a strong will to develop local forms of cultural expression. As Santos Zunzunegui says in relation to the films of the first amateur filmmaker to film in Euskera, Gozton Elorza, “It is a work that emerges out of a determined didactic will, where artistic efforts count less than the struggle to make evident the importance of audiovisual media” (Zunzunegui 1983, 226). With this in mind, the Basque Amateur Cinema project seeks to become a pedagogical tool that not only rescues a forgotten film heritage, but also becomes an open resource for anyone interested in completing the global map of amateur cinema.

Bibliography

George Toles. 2010. “Rescuing Fragments: A New Task for Cinephilia.” Cinema Journal49 (2): 159–66.

Lauzirika, Arantza, and Natxo Rodríguez, eds. 2017. 40 Urte Zinea Eta Euskara Bultzatzen. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco = Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea.

Letamendi, Jon, and Jean-Claude Seguin. 1997. Los orígenes del cine en Alava y sus pioneros (1896-1897). Vitoria: Ayuntamiento de Vitoria-Gasteiz : Filmoteca Vasca : Fundación Caja Vital Kutxa.

López Echevarrieta, Alberto. 1984. Cine vasco, de ayer a hoy: época sonora. Colección Cinereseña. Bilbao: Mensajero.

Zunzunegui, Santos. 1983. “En los comienzos del moderno cine vasco: Gotzon Elorza.” Kobie, no. 1.

———. 1985. El cine en el País Vasco. Bilbao: Diputación Foral de Vizcaya.