The very fact that [film] societies are operated by volunteers… contributes to their unique atmosphere. An unimposed mutual interest first brings the ‘evangelists’ together; it drives them continually to explore and search out films of artistic and historic merit which otherwise might remain unknown and unseen; it urges them to find audiences in living-rooms, halls and theatres; it can stimulate them to study and discuss, often to write, and sometimes even to make films. — Dorothy Burritt, 1959[1]

In Vancouver, British Columbia, during the late 1930s and 1940s, Dorothy and Oscar Burritt were two such “evangelists” whose enthusiasm for cinema led them to make films. The Vancouver Branch of the National Film Society of Canada was organized in 1936 to promote the appreciation of motion pictures, both as art and as entertainment. The society gave Vancouverites a unique window into non-mainstream cinema — classic silent movies, foreign films, and documentary and experimental works. Its film fare was eclectic and often challenging. The society grew surprisingly in the late 1930s, with a paid membership of 1,000 or more. The popularity of its screenings is confirmed in a short film that documents a Sunday afternoon show at the Stanley Theatre in April 1940.[2]

Some of the amateur films produced by society members in Vancouver transcended their creators’ modest intentions, and provide early evidence of an artistic sensibility in western Canadian cinema. Fortunately, these long-forgotten works have been preserved, and can be found in Canadian archival collections.

In the late 1930s, Dorothy Fowler (1910-1963), a UBC student and film society member, met Oscar C. Burritt (1908-1974), a mainstay of the society and an avid amateur filmmaker. In 1939, Oscar and four other amateurs would make an impressive silent documentary entitled Stanley Park (restored and preserved by the BC Archives). By 1943, he was steadily employed as a cinematographer for Vancouver Motion Pictures Limited (VMP), one of the city’s pioneering production companies. Before long he was directing industrial films like Salmon for Food and The Herring Hunters (1945), as well as shooting and directing some of the documentary shorts that VMP produced under contract for the National Film Board. (For example: Tomorrow’s Timber, 1944; Salmon Run, 1945; Of Japanese Descent, 1945.)

Dorothy and Oscar married on January 10, 1942. Oscar’s VMP colleague Lew Parry recalled Dorothy as “something of an artiste” who was interested in “arty things, arty groups, discussions on philosophy and all that sort of thing.” [3] Not unlike the collaboration of Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid on Meshes of the Afternoon, the pairing of Dorothy and Oscar brought together her sense of drama and visual style with his wit and cinematographic skill. Their partnership produced a few obscure but delightful treasures of Canadian independent filmmaking.[4]

Their first completed film, Three There (1940), records a long weekend on Galiano Island in the Strait of Georgia with their friend Margaret Roberts. Although on first appearance nothing more than a well-photographed holiday keepsake (with the requisite posing, repetition and waving to the camera), Three There is actually a little essay in using film to create a sense of place and mood. The action of waves and the passing of steamships mark the languid rhythm of “island time” as the three friends wander along country roads, relax in a cottage, visit neighbours and play on the beach. In a series of striking vignettes, Dorothy is seen dancing, reclining in the tall grass, and performing dramatic Martha-Graham-like gestures in a suspended mirror. Viewing the film is somewhat like listening to the ambient music of Brian Eno (which would in fact be the perfect soundtrack). As elsewhere in Dorothy’s work, there are strange similarities to Maya Deren’s visual style—although Deren would not make her seminal first film Meshes until 1943, some three years later. Especially evident throughout Three There is the affection and humour shared by the trio.[5]

At around the same time, Dorothy collaborated with Margaret Roberts to produce the collage film “and–”, the earliest known attempt at experimental filmmaking in Vancouver, and among the earliest in Canada. “and–” is partially composed of material culled from Oscar’s late-1930s footage. This found footage—including negative and inverted (reversed) images and wild camera movements—is combined with painted and scratched stock, and a section where holes punched in the frame have been filled with other images. The result is refreshingly chaotic. From an ominous opening shot of a large metal cylinder rolling toward a fragile glass figurine, the film hurtles headlong through segments of increasingly frenetic rhythmic montage to its abrupt conclusion at a stop sign. Local landmarks appear upside-down, and both Oscar Burritt and Margaret Roberts put in cameo appearances. Preserved today in silent form[6], the film was originally presented with a soundtrack of jazz music from phonograph records: Benny Goodman’s “Sing, Sing, Sing” and Bud Freeman’s “China Boy” and “The Eel,” mixed “live” on dual turntables.[7] The technique of painting and scratching directly onto film would later become widely identified with Norman McLaren of the National Film Board of Canada. However, Dorothy and Margaret were almost certainly inspired by the earlier work of Len Lye, whose pioneering short A Colour Box (1935) had been screened by the film society.[8]

Another collage film somewhat similar to “and—“, residue 2 (n.d.), was found decades later among Oscar Burritt’s possessions. It is credited to one Angus Hanson, but it seems very likely that this name was a pseudonym used by Oscar Burritt. It is a mysterious little film—and perhaps it was made to be just that.[9]

Both “and–” and residue 2 can now be viewed on YouTube with newly-added musical scores.

The Vancouver Branch of the National Film Society had been inactive during the Second World War. In 1945-46, however, Dorothy Burritt, Moira Armour and Vernon van Sickle joined forces with painter and Vancouver School of Art instructor Jack Shadbolt to continue the screenings. Collaborating with the short-lived Labor Arts Guild, they presented an impressive series featuring more than 60 cinema classics. It is worth noting that this series included key works by Luis Bunuel, Sergei Eisenstein, Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau—an ambitious program for any film society, even today.[10] The series attracted a new generation of film lovers. One of these was Stanley Fox, an 18-year-old UBC student and film buff. Dorothy encouraged his filmmaking efforts, especially Glub (1946), a slapstick parody of the films of Maya Deren.

Stan Fox also collaborated with Dorothy on what would be her most complete and personal cinematic statement—Suite Two: A Memo to Oscar (1947). In 1946, Leon Shelly’s production operation had moved to Toronto, where it became Shelley Films; Oscar went east to continue working for the company. Dorothy, who remained behind temporarily in Vancouver, conceived Suite Two as a present for her husband: a memento of their old home at Suite 2, 1960 Robson Street, near Stanley Park. It was part of an old mansion that would soon be demolished. Like Three There, the film transcends its simple objective, and in so doing provides an amusing glimpse of a unique milieu.

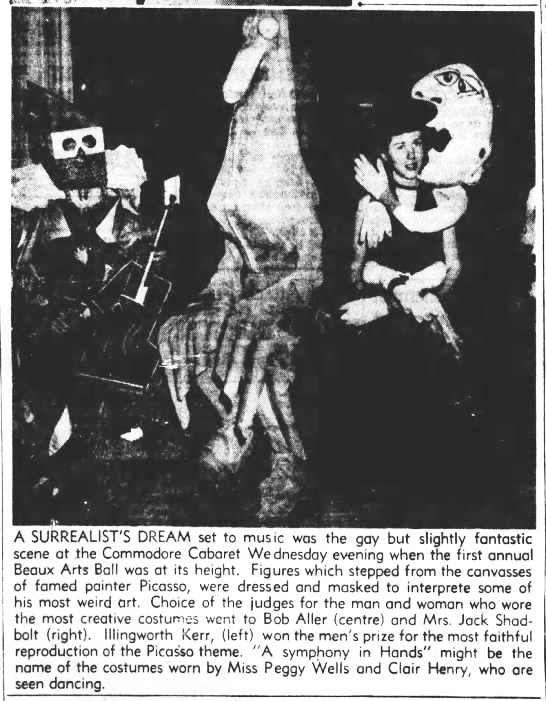

Suite Two is an offbeat study of light and life at their apartment, and the circle of artistic friends they entertained there. Entering through a window, the roving camera watches Dorothy arise, brush her hair, tidy the apartment, drink coffee, and sit for a formal portrait. In the evening, several friends (including film editor Maureen Balfe, librarian Moira Armour, and clairvoyant Nettie Gendall) drop in for drinks, dancing, spirited conversation and a screening of a French feature film, Sacha Guitry’s Pearls of the Crown (1937). Refreshments are served by Dorothy’s “butler”: an enigmatic figure in a bird costume that resembles a grotesquely Moderne-styled forerunner of “Big Bird.” This was an award-winning costume from that year’s Picasso-theme Beaux Arts Ball, an annual celebration staged by students from the Vancouver School of Art.[10a]

The most intimate of the Burritts’ films, essentially made for an audience of one, Suite Two is perhaps the most satisfying as well. Its modest aim—to depict a person, a living space and a milieu—is so charmingly achieved that the film fascinates complete strangers 70 years later. Due to its very specificity—recording this particular person, this room, these curios, and this gathering—the film achieves a degree of “universality.” One can only envy the Burritts the pleasure they took in their friends, and enjoy the spirit in which the film captures it. Suite Two received Honourable Mention in the amateur category at the very first Canadian Film Awards presentation in 1949.[11]

As Stan Fox recalled in a 1988 interview:

Well, this was really Dorothy’s film. She had thought it up as a memento of her apartment and a present for Oscar—and a recording of those friends, y’know, at that time—and asked me if I would film it. That’s really how it happened. ... It was her idea to make Suite Two as a kind of a memento of this apartment, which was going to be destroyed. In those days, they were just beginning to destroy the West End [of Vancouver]; and it was slated to go, to be replaced with an apartment house. And they knew that, so that’s why the film was made.[12]

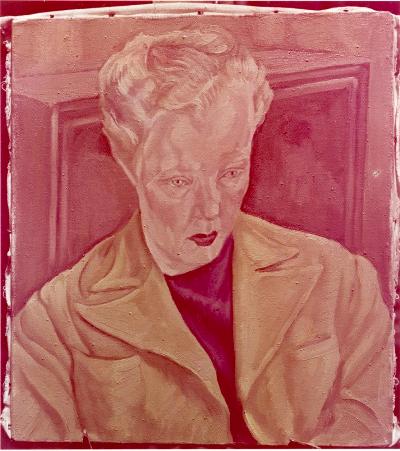

In an interlude before the party, artist Peter Bortkus (1906-1995) is shown painting Dorothy’s portrait. Born in Tallinn, Estonia, Bortkus was active during the years 1930-1947 in Vancouver, where he was befriended and influenced by Frederick H. Varley, a famous member of the Group of Seven. By contrast, Bortkus was a little-known figure; he painted prolifically, especially in the field of portraiture, but his work was not exhibited to any significant degree. In 1947, he relocated to Toronto, where he supported his family by working as a commercial artist. The original Bortkus painting of Dorothy has since disappeared. If it still exists, the current owner may not be aware of the subject’s name, or of her significance to Canadian film history. In 1990, however, Douglas S. Wilson, a Toronto friend of the Burritts, was able to provide the BC Archives with this colour photo of the painting.

When asked four decades later for his own assessment of Suite Two, Stan Fox replied:

Oh, I like it. I’m surprised. I think it’s a very interesting piece of film, in its way. As you say, the atmosphere is very charming, and seems to have lasted; it says something about the era, you know. I think people here in BC are particularly vulnerable to forgetting the past, or else looking at the past as being just a very quaint thing—something that was definitely not as sophisticated as the present.

Fox also provided this vivid recollection of Dorothy Burritt and her milieu:

There seemed to be, in Vancouver, a very sophisticated group of people, most of whom knew each other, that seemed to “feed” on each other, and keep each other abreast of what was happening in the rest of the world. ... Dorothy herself was a very influential person, because she was very involved with the arts and had a very good sense of values about things of an aesthetic nature. And I think that I was really in the middle of almost an “artists’ colony”—although there weren’t a great many practicing artists. There were certainly an awful lot of people who really lived for things artistic, whether it was painting or film or books or whatnot.

She was a very kind person. I had the impression she was very cultured, very well-educated, and seemed to know an awful lot about a lot of things. And she was a very supportive person. I think that was perhaps her strongest characteristic; when she saw something that she felt had some kind of value, someone’s talent, she encouraged it. In terms of music and art and cinema, [Dorothy and Oscar introduced me to] what you’d call “the modern era”; what was happening, and what was important, in those arts. Plus, I think even more than that, it was an attitude to life—a sense of the importance of the arts in life, and making the arts a focus in your life that was much more important than making money. And considering the society they were living in at the time, they were remarkable people.

Stan’s perspective on Dorothy was echoed by his childhood friend Allan King (1930-2009), a celebrated director of Canadian documentaries (Skidrow, Warrendale, A Married Couple) and feature films (Who Has Seen the Wind, Termini Station).

[Dorothy was] extraordinarily cultured; Romantic, in the sense of a “Romantic Artist”; absorbed in the life of the artist, all the things that one read books about; a sort of an echo of Bohemia, of a life that was unconventional, not like bourgeois Kerrisdale or lower-middle-class Kitsilano. It was a whole world of people apart, people who did Romantic and exciting things. And I should clarify the word “Romantic”. By that, I mean “idealized“, in the sense that it’s not a real perception of what Dorothy was like. I don’t know what Dorothy was like. I knew her then as a person I thought about who represented something; an ideal kind of figure to do with the arts, to do with creativity, to do with things that were really important, not trivial things like delivering groceries or delivering newspapers, or whatever it was that one picked up one’s spare change from.

The other thing that was very important about Dorothy and such people—but [that] I remember particularly with her and about film—was the whole notion of excellence, the whole notion of aspiring to do one’s best, to do extraordinary work. ... Dorothy was very powerful in talking about and advocating original work, and being open to original work is really fundamental to doing good work. It’s fundamental to keeping one’s self vital in any way. That kind of vitality is a hallmark, and something that, for me, made her invaluable.[13]

The film society officially regrouped in 1947, and in 1950 became the Vancouver Film Society, which operated until the mid-1970s. Fox and King, then employed at CBC Vancouver, both served on its board.[14]

Settling in the east, the Burritts helped to create the Toronto Film Society. Oscar left Shelley Films in 1950 to join the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, where he supervised the television film distribution and editing services and trained film personnel. In the 1960s, he also introduced broadcasts of classic films on CBLT Toronto.

In 1951, when the society brought Maya Deren to Toronto to produce a dance film, Moira Armour and Dorothy Burritt directed the TFS workshop that collaborated with their famous visitor. The uncompleted project, Ensemble for Somnambulists, was shown only once in Toronto. Dissatisfied with the film, Deren never released it. She would later rework the idea as The Very Eye of Night (1952-58).[15]

Dorothy was also a co-founder of the Canadian Federation of Film Societies (CFFS), and did much to promote the awareness of film as art in Canada. Unfortunately, the couple’s interest in making films lost out to their institutional activities. They continued to shoot home movies, but these largely lacked the playful artistry of their Vancouver films.[16]

The Burritts’ contribution to the film society movement was recognized by a special Canadian Film Award in 1963, just a few months before Dorothy’s death. Shortly afterwards, the CFFS established The Dorothy Burritt Memorial Award (later renamed for Dorothy and Oscar Burritt), an annual cash grant to support projects that contributed “to greater understanding and enjoyment of film as an art”.

It seems very fitting that they be remembered in such a way.

NOTE: This article was adapted from four posts written for my (now-defunct) Royal BC Museum staff profiles blog, one from 2013 and three from 2016-17. The third of these posts, “Evangelist: The Films of Dorothy Burritt,” was my contribution to The Early Women Filmmakers Blogathon, which was hosted by Movies Silently.

© 2016-2019 by Dennis J. Duffy

NOTES:

[1] Dorothy Burritt, “The Other Cinema,” Food for Thought, vol. 19 no. 6 (March 1959), 265.

[2] This 16 mm footage, shot by Oscar Burritt and Milt Holden, is BC Archives item AAAA2047 at the Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM) in Victoria, BC.

[3] Lew Parry interviewed by David Mattison, 11 June 1981; audio tape no.T3855:0004, BC Archives, RBCM.

[4] Biographical information about Oscar Burritt and Dorothy (Fowler) Burritt was supplied by Douglas S. Wilson of Toronto in his correspondence with the BC Archives’ moving image archivists, 1981-1990, and by Stanley Fox and Don Lytle in conversation with the author.

[5] Three There is preserved at Library and Archives Canada (LAC), Ottawa. The RBCM holds a video reference copy, which is BC Archives/RBCM item AAAA2879.

[6] “and–” is also preserved at LAC. The BC Archives/RBCM holds a video reference copy, BC Archives item AAAA0004.

[7] Margaret Roberts, personal communication, 1986.

[8] Dorothy Burritt, “The Other Cinema,” 263.

[9] Dennis J. Duffy, “Report on the Film residue 2 by Angus Hanson,” unpublished typescript, 1990. An analog video master of residue 2 is held by the RBCM as BC Archives item AAAA2556.

[10] Jack Shadbolt, “A Personal Recollection,” in Vancouver : Art and Artists, 1931-1983 (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1983), 41. Shadbolt recalls Dorothy Burritt as a “fanatic” on the subject of cinema.

[10a] Stan Fox, personal communication. See also John Mackie, “Partying at the Commodore with the Motifs Picasso, and Jack Shadbolt,” Vancouver Sun, July 25, 2019. Read the Mackie article online.

[11] The edited camera original of Suite Two: A Memo to Oscar is preserved at the RBCM as BC Archives item AAAA2810.

[12] Stan Fox, interviewed by D.J. Duffy, Victoria, 20 June 1988: audio tape no. T4349:0001-0004, BC Archives, RBCM.

[13] Allan King, interviewed by D.J. Duffy, Vancouver, 13 September 1991; author’s collection.

[14] Societies file no. 2279, “Vancouver Film Society,” B.C. Registrar of Companies files, BC Archives. The society was dissolved in 1953, but a second incarnation was active from 1955 through the early 1970s.

[15] Herbert Whittaker, “Show Business,” Toronto Globe and Mail, 3 October 1951, 9; John Porter, “Artists Discovering Film: Postwar Toronto,” Vanguard, Summer 1984, 24. Ensemble for Somnabulists was finally published as an “extra” on the Zeitgeist Films DVD release of Martina Kudlacek’s documentary In the Mirror of Maya Deren (2002). Dorothy Burritt and Moira Armour are credited in Ensemble under “production assistance”.

[16] One of Oscar’s few completed films from this period is Cinemaorgy (1955), which documents the Toronto Film Society’s 1955 annual field trip to George Eastman House at Rochester, New York. It is also preserved at the LAC; the RBCM holds a video reference copy, BC Archives item AAAA1125.