Amateur Cinema, Avant-Garde Film, and Tendency Film

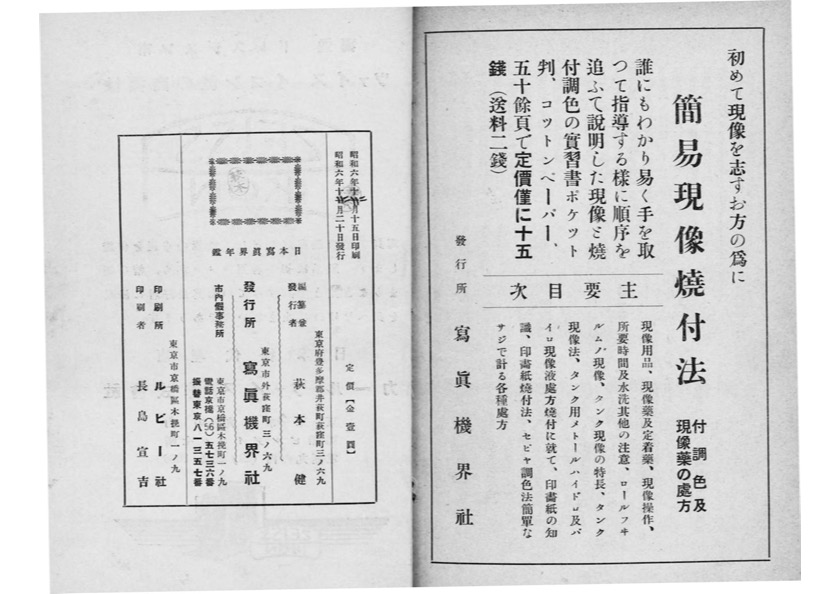

Amachua eiga no seisaku: Riron to jissai (Tokyo: Nippon Amachua Eiga Kyōkai, 1933)

by Kawamoto Masao (translated by Noriko Morisue)

Amachua eiga no seisaku: Riron to jissai (Tokyo: Nippon Amachua Eiga Kyōkai, 1933)

The given subjects range very broadly, and all of them must be discussed in relation to the essence of the theory of film art. Moreover, the subjects I will deal with are those whose answers are attainable only after digging into the most cumbersome perspectives of society and the world. Because of this, and the limited number of pages, I should tell you in advance that this essay sheds light on the topic only from concepts. Since I am expected to write an essay specifically in relation to amateur small-gauge film, I will examine my subjects through a very unilateral approach.

Let me first clarify the concepts of my primary subject.

“Amateur cinema” is a broad term encompassing mainly 16mm and 9.5mm films. But we should stop debating the width of film gauges here. Instead, I will interpret and discuss “amateur cinema” as a broad concept.

The term “avant-garde film” concerns [films that are] thoroughly non-descriptive, and its concept is also extremely ambivalent. But here, following the worldly custom, I would like you to interpret it as French avant-garde works, as well as films that pursue the same mode of art.

“Tendency film” is likewise a very ambiguous term, but here I shall define it as a proletarian film that strictly imposes socialist objectives.

My introduction was rather long, but I defined these terms above because both avant-garde film and tendency film cast strong influences on amateur filmmakers in our country today. These two contrasting trends have increasingly been discussed as the directions that amateur cinema should take, and they should indeed be discussed that way.

I would first like us to consider what kind of significance avant-garde film has on amateur filmmakers.

Today, avant-garde film is thought to encompass so-called pure films (jun’sui eiga) and absolute films (zettai eiga), which have been discussed actively since the successive introduction and importation of a series of French avant-garde films last spring, such as Man Ray’s L’Etoile de Mer, Germaine Dulac’s La Coquille et le clergyman, Dimitri Kirsanoff’s Brumes d’automne, as well as Alberto Cavalcanti’s En rade and Rien que les heures. Pure film and absolute film are the mode of art that has been creating a sensation in Germany and France over the last decade through the works of modern painters, musicians, poets, and writers. Besides the artists listed above, many others belong to this category, including Fernand Léger, Moholy-Nagy, Marcel L’Herbier, Walter Ruttmann, Paul Richter, and Henri Chomette. I have listed them altogether in a rough manner, but in reality, there are slight differences in the assertion, emphasis, and pathways between absolute film, which emerged primarily from Germany, and pure film, which is primarily rooted in France. And yet, they share the most significant characteristic, which allows for expression that transcends time and space by means of a mechanism called a camera lens. They aim to grasp a sense of free observation and free sensibilities. They are the ecstasies of cinema’s new and powerful play of light, as well as the extreme heightening of the beauty of flows through cinema’s construction, just as is done in music.

Yet, when they are critiqued from the correct standpoint of a social scientific view of art, they are apparently no more than the pleasure of personal experience or individualistic thought. A vivid sense of freedom is no more than the self-gratification in indulging one’s unhinged feelings. If they say that interpretation needs not be given [to the works], that it is enough to let them feel, this notion will only mean an irredeemable inundation of individual perceptions.

But on the other hand, amateur filmmakers should pay sufficient attention to the non-commercialization of cinema that avant-gardists strove to achieve—in other words, their intention to break all the conventions of commercial cinema in order to pursue filmmakers’ original films and the realization of new creative desires. This is one of the most important fundamental concerns that can and must be addressed as an issue of amateur film. One of the lessons here is to take advantage of all the possibilities that the amateur status can offer. At the same time, consideration and warning must be given once again to the self-serving pleasure of the avant-garde.

It is important to note that avant-garde cinema has actually taught us about a new direction for [the use of] the cine lens and the beauty of flows in cine composition. Amateurs must not use the camera lens by old rules and customs. The avant-garde has also taught us that the composition of amateur cinema must absorb a more vivid dynamism. Meanwhile, we must take precaution against the adverse custom of so-called imitative mannerism. Since the introduction of avant-garde film, there have been a few negative tendencies in amateur cinema, such as meaningless camera positions and angles, as well as absurd editing techniques.

Meanwhile, tendency film is associated with the most notable leftist film movement that emerged exceptionally rapidly in the past few years. We must say this is an inevitable product of the times. This movement fully developed as a result of Prokino—the only Proletarian Film Movement organization in Japan — making a few films every spring for the past few years. The only key to understanding this movement is to correctly grasp and practice [filmmaking] with the acknowledgment that proletarian films must be produced by the hands of proletariats. The beginning of this movement faced various criticisms and much pessimism from the general public over their 16mm and 9.5mm films, but their bold and practical filmmaking movement overwhelmed all these criticisms, and impressively opened up new prospects. To this day, films by Prokino—including Dorei sensō (Slave War), Tochi (Earth), Kōwan rōdōsha (Wharf Laborers), Mēdē (May Day), and Prokino News—do suffer from issues such as the obvious lack of financial resources and the immaturity of technical training. However, they have exhibited the real beauty of cinema in ways that prior films could not, and they have made appeals for a correct understanding of society and the world. They strongly show and advocate the right direction for the future of cinema. Amateurs are expected to recognize the fact that they are constituents of society, and to teach this more strongly than anything else. Their films teach amateur filmmakers themselves that small-gauge cinema, such as 16mm and 9.5mm, can be useful as a sufficient, powerful weapon. For those who seek the right path for amateur film, this is where the correct implication can be found.

Let us put aside the many small and deceptive tendency films, which ingratiated themselves with the masses and were made by production companies that quickly saw business opportunities in the large currents of the zeitgeist at the time when these proletarian films were made. In the spring last year, a small number of Soviet films were imported: Eisenstein’s Old and New, Dovzhenko’s Earth, Kaufman’s In Spring, and so on. In addition, Soviet film producers and critics—who, besides those listed above, include Lunacharsky, Pudovkin, and Vertov—generated many discussions by introducing social-minded film theories, which have taught us a number of crucial lessons. In particular, the study of film composition, sparked by the term “montage,” is a dynamic element that facilitates a fundamental understanding of cinema and its development. This is also where amateur filmmakers are expected to obtain correct understanding.

I hope I have demonstrated, however roughly, the connections between amateur film, avant-garde film and tendency film. Let me conclude by advising amateur filmmakers that, while film is “a means of freedom,” it is not in any way a toy for amusement, nor is it the throes of strangled capitalism.